Research

- Job stress theories and models, the DISC-R Model in particular (see next section)

- Recovery at work, mental recovery in particular (psychological detachment)

- Recovery and sleep

- Employee creativity and innovative behavior

- Vitality at work

- Employee sustainable performance

- Psychological safety at work and psychosocial safety climate (PSC)

- Counterproductive work behavior

- New ways of working / hybrid work / flexible office

- Social innovation and sustainable employability

- Sports psychology: athlete motivation and performance, (mental) recovery, sleep patterns, mental training, sports injuries, obsessive and harmonious passion for sports

Special focus: The Demand-Induced Strain Compensation Recovery (DISC-R) Model

Around 2000, Jan de Jonge and Christian Dormann intensively discussed the lack of empirical evidence for the stress-buffering role of job resources in so many job stress models. The quest for combinations of specific job demands and corresponding job resources that are particularly suited to predict job strain was one of the triggers of the development of their Demand-Induced Strain Compensation (DISC) Model. Their thoughts and refreshing ideas were first published as a theoretical reflection (de Jonge & Dormann, 2003) and subsequently empirically confirmed in two seminal papers (de Jonge et al., 2004; de Jonge & Dormann, 2006). DISC theory unifies principles that are common to the more classic models, and claims to be a more comprehensive theory of job stress and work motivation than other theories. To summarize briefly, DISC theory is largely based on self-regulation theory (cf. Baumeister et al., 2007) and Lekander’s (2002) homeostatic regulation theory derived from immunology and neuroscience. Self-regulation refers to the self altering his/her own responses or inner states (Baumeister et al., 2007). Usually this takes the form of overriding one response (or behavior or inner state) and replacing it with a more desired response. What makes DISC theory rather unique is that it deals with functional self-regulation at work expressed in the so-called matching hypothesis (de Jonge et al., 2008). Similar to homeostatic regulation in the immune system and nervous system, DISC theory proposes that individuals activate functional, corresponding job-related resources to alter the effects of specific job demands. Furthermore, DISC theory elaborates on the idea that measures of job characteristics need to be specific and targeted rather than broad and general in order to find the proposed moderating effects of job resources.

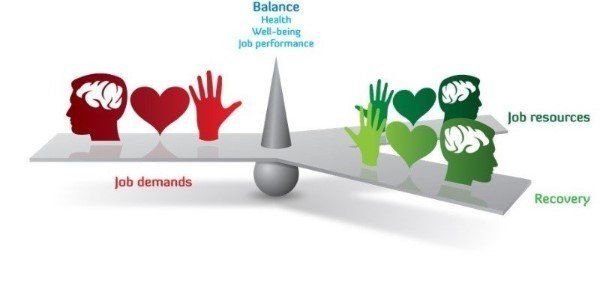

The original DISC Model (de Jonge & Dormann, 2003; 2006) is particularly premised on two key principles, namely (1) multidimensionality of constructs, and (2) the triple-match principle (or TMP). Crucial and initial components of the DISC Model are job demands and job resources. Job demands are defined as work-related tasks that place short-lasting or persistent requirements upon workers, and that require physical and/or psychological effort to meet the tasks. Job resources, on the other hand, are instrumental or psychological means at work that can be employed to deal with job demands.

With respect to the multidimensionality principle, the DISC Model distinguishes three specific types of job demands, job resources, and job-related outcomes. More specifically, the model proposes that job demands, job resources and job-related outcomes may each contain cognitive, emotional and physical elements. As far as job demands are concerned, three types can be distinguished: (1) cognitive demands that impinge primarily on the human information processing; (2) emotional demands, mainly concerning the effort needed to deal with organisationally desired emotions during interpersonal transactions; and (3) physical demands that are primarily associated with the muscular-skeletal system (i.e. sensorimotor and physical aspects of behaviour). Similarly, job resources may have a cognitive-informational component (e.g., colleagues or computer systems providing information), an emotional component (e.g., colleagues providing sympathy, affection, and a listening ear) and a physical component (e.g., instrumental help from colleagues or ergonomic aids. Finally, in a similar vein to demands and resources, job-related health, well-being, and performance-based outcomes may also comprise cognitive, emotional and physical dimensions. These outcomes can be either negative or positive. For instance, concentration problems and employee creativity represent cognitively laden outcomes, emotional exhaustion and positive affect represent emotionally laden outcomes, and physical health complaints and physical strength can be reasonably assumed to mainly reflect bodily sensations (i.e. physical outcomes).

The second key principle is the triple-matching of concepts (i.e. matching demands, resources, and outcomes). The triple-match principle, or TMP, proposes that the strongest, interactive relations between job demands and job resources are observed when demands and resources and outcomes are based on qualitatively identical dimensions. For instance, emotional support from colleagues is most likely to moderate (i.e. mitigate) the relation between emotional demands (e.g., irate customers) and emotional outcomes (e.g., emotional exhaustion). So, the TMP suggests not only that job demands and job resources should match, but also that both job demands and job resources should successively match job-related outcomes. To summarize, the complementary fit of the TMP applies to three different levels: (1) the match between job demands and job resources; (2) the match between either job demands or job resources and job-related outcomes; and (3) the match between job demands and job resources and job outcomes.

Finally, it should be noted that the TMP is a so-called probabilistic principle . This means that TMP effects are considered to be more likely in empirical research studies than non-matching effects, but the model does not argue that such non-matching effects should not occur at all. As mentioned before, the focus of interest is on associations between specific job demands on the one hand, and ‘matching’, 'less-matching' and even ‘non-matching’ job resources on the other hand. Findings other than triple-matches are therefore no counterevidence to the DISC Model.

Beyond DISC: Integration of detachment from work

So far, the DISC Model has mainly focused on processes occurring at work. However, it might not only restrict itself to the work situation. Experiences and events happening off the job may also be related to employee health and well-being. Specifically, research on recovery has shown that recovery experiences during non-work time interact with job demands and job resources in the prediction of employee health and well-being (Sonnentag et al., 2022). Most recovery studies, however, did neither systematically test the interaction between job demands, job resources, and off-job recovery, nor differentiate between the cognitive, emotional, and physical aspects of demands, resources, and recovery. Thus, extended DISC theory goes beyond recovery research by describing specific combinations of job demands and resources on the one hand, and off-job recovery on the other. Gaining knowledge about how job demands, job resources, and off-job recovery are related to employee outcomes is highly relevant for both theory and practice.

The extended DISC Model, expressed in the DISC-R (R for recovery) Model, was introduced by de Jonge and colleagues in 2012 (de Jonge et al., 2012) and generally focuses on the recovery concept of detachment from work. Detachment can, in general, be seen as the most promising strategy as far as job-related recovery is concerned (Sonnentag et al., 2022). Etzion and colleagues (1998, p. 579) defined detachment from work as an ‘individual’s sense of being away from the work situation’. It is an experience of leaving one’s work behind when returning home (i.e., ‘switching-off’ through off-job recovery). Low detachment from work implies that the functional bodily systems remain in a state of prolonged activation. To recover from high job demands, it is important that employees ideally engage in off-job activities that appeal to other systems or do not engage at all in effort-related activities (Geurts & Sonnentag, 2006). For instance, a healthcare worker whose job requires high emotional effort would be better off avoiding engagement in off-job activities that put high demands on the same (i.e., emotional) systems. Similarly, a construction worker with a highly demanding physical job would be better off avoiding engagement in activities after work that put high demands on the same (i.e., physical) systems. Off-job recovery refers to the process where cognitive, emotional, and physical systems that were activated on the job unwind and return to their baseline levels (Sonnentag et al., 2010). The recovery process can be regarded as a process opposite to the strain process. It is therefore assumed that detachment from work should encompass a cognitive, emotional, and physical switch-off from work, which is in line with the three DISC dimensions. To assess the three types of detachment from work, the so-called DISQ-R(ecovery) questionnaire had been developed (cf. de Jonge et al., 2011). In agreement with theory about the role of off-job recovery in the job stress process (Sonnentag et al., 2022), the DISC-R Model proposes that detachment from work has an additional, moderating, effect in the relation between job demands, job resources, and employee outcomes. Furthermore, in line with earlier DISC and recovery theory, it is assumed that detachment from work that matches particular demands will be most effective (e.g., cognitive detachment in relation to cognitive demands).

How to measure its key components?

To assess the six types of job demands and job resources, the so-called DISC questionnaire, labelled DISQ (Q for Questionnaire), had been developed (cf. Bova et al., 2015; Balk et al., 2018). The DISQ is available in several languages, in survey and diary studies, in full and short versions, in work, home, and sport editions, and can be downloaded here: DISQ. Furthermore, the DISQ-Recovery questionnaire can be downloaded here as well.

How to test the DISC(-R) Model empirically?

In general, we used multiple regression analyses (MRAs) in a hierarchical way to examine assumed associations between demands, resources, recovery and outcome measures, for instance using IBM SPSS® for Windows. In the case no significant violations of linear regression assumptions were detected, the MRAs were performed with forced entry of variables within each hierarchical step (cf. de Jonge et al., 2019). In the first step, we introduced demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, and education) and standardized main terms of demands and resources (and eventually recovery). In the second step, we tested moderating effects of resources by adding multiplicative interaction terms of standardized demands and resources (and recovery) into the MRAs (cf. Aiken & West, 1991). Two different series of MRAs were carried out due to the relatively large number of possible interaction effects in one single analysis. In line with suggestions of de Jonge and Dormann (2006), we split the analyses into matching and non-matching demands-resources interaction testing. So, the first series of MRAs tested triple-matches and double-matches of common kind for each outcome measure, respectively. The second series of MRAs tested double-matches of extended kind and non-matches for each outcome measure, respectively. Furthermore, if a significant moderating effect is in agreement with our theoretical framework, it is tagged a theoretically valid triple-match, double-match, or non-match. However, if a significant moderating effect is not in line with our framework, it is tagged a theoretically non-valid triple-match, double-match, or non-match (cf. van den Tooren et al., 2011). Following the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991), moderating effects were graphically represented with the help of an Excel template. In addition, slope significance tests of the simple regression lines were performed as recommended by Dawson and Richter (2006). SPSS syntax templates can be downloaded here: SPSS.

Empirical evidence for the DISC(-R) Model

Since 2003, the DISC Model has been tested in different kinds of empirical studies in lots of countries. These studies encompass all types of research designs, such as cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys, daily diary studies, multi-level studies, intervention studies, as well as psychometric, vignette, and laboratory studies. Different kinds of employees were used, although the majority of them were human-services workers such as nursing, retail, and teaching staff. Even university students (e.g., de Jonge & Huter, 2021), professional athletes (e.g., Balk et al., 2018), and recreational runners (e.g., van Iperen et al., 2022) were study subjects. In 2011, two distinctive research groups conducted independent narrative review studies in different occupational groups from different countries to evaluate the empirical evidence for the TMP. They revealed that the TMP received empirical support to a large extent (van den Tooren et al., 2011; van de Ven, 2011). Both studies showed that in general triple-matches were more likely to be found than double-matches or non-matches. The overall outcome of these reviews indicated that matching job resources are more functional than less-matching and non-matching job resources to deal with specific types of job demands as far as the stress-buffering effects of those job resources are concerned. Both reviews did not lend strong support with respect to the so-called activation-enhancing effect of (matching) job resources (i.e., the model’s balance mechanism). One reason for the latter finding is that there were not so many studies available that investigated this effect at that time. More recent empirical studies testing the activation-enhancing mechanism are largely in favor of this effect (e.g., de Jonge et al., 2019; de Jonge & Huter, 2021).

Furthermore, several studies tested the assumptions of the DISC-R Model (e.g., de Jonge et al., 2012; Niks et al., 2017; Balk et al., 2017). Most notably a study by de Jonge and colleagues (2012) among 399 Dutch human services employees from three organizations detected moderating effects of matching job resources as well as matching off-job recovery (i.e., detachment from work) on the relation between corresponding job demands and employee outcomes. Specifically, results showed that cognitive detachment from work was negatively related to learning and creativity, whereas emotional and physical detachment from work were positively associated with employee health and creativity. Similar effects of cognitive detachment from work on employee creativity were also found in a daily diary study by Spoor et al. (2010). A DISC-R daily diary study among 73 Dutch elite athletes showed that moderating effects of daily detachment occurred more often when there was a match between specific types of sport demands, detachment, and recovery state rather than when there was less match or no match (Balk et al., 2017). Finally, Niks and colleagues (2018) tested the DISC-R Model using a three-wave quasi-experimental study with intervention and comparison groups in hospital care. The implemented intervention (called ‘DISCovery’) aimed at improving employee health/well-being by optimizing the balance between job demands, job resources, and off-job recovery. Positive changes were found for members of the intervention groups, relative to members of the corresponding comparison groups, with respect to job demands, resources, as well as health, well-being, and performance outcomes. Overall, results provided support for the effectiveness of the DISCovery method in hospital care.

Where to find most DISC(-R) literature?

You will find most updates of DISC theory in our latest book chapter:

Jonge, J. de, Demerouti, E., & Dormann, C. (2024). Current theoretical perspectives in work psychology. In M. Peeters, J. de Jonge, & T. Taris (Eds.), An Introduction to Contemporary Work Psychology Second Edition (pp. 118-144). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Moreover, many theoretical and empirical papers, book chapters, and theses regarding the DISC-R Model can be downloaded here: